神了-29年前外媒刊登的一篇文章在今天得到应验

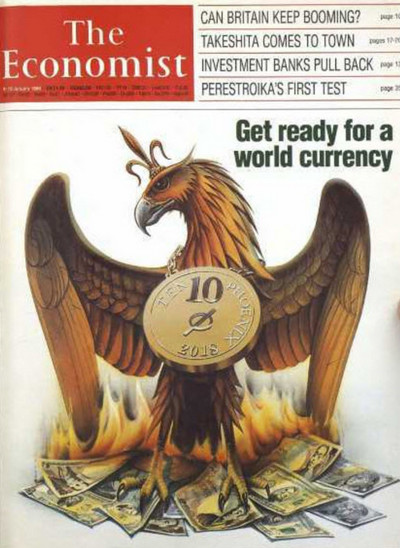

以下这篇文章是29年前由《经济学人》刊登的。大约6个月前它被重新发表。而在今天,这篇文章又再次被刊登。

29年前的经济学人封面 从现在开始起的未来三十年中,美国人、日本人、欧洲人,以及来自全球其他富裕国家的人们,还有部分来自经济相对不发达国家的人们,可能会用同一种货币来为自己的消费买单。未来,人们衡量价格或价值的工具将不再是美元、日元或者德国马克等等,很有可能的选择就是凤凰币——一种正在浴火重生的数字货币(说的跟今天的比特币极其相似)。未来,凤凰币将会越来越受到企业和消费者们的青睐,因为与今天各国发行的纸币相比,数字货币的使用将会更加便捷。从目前的发展趋势来看,这种新型货币似乎会成为打破人类过去2000年经济生活模式的一种古怪的原因。 如果是在1988年初时,这种预测似乎是一种非常古怪的想法。 关于最终货币联盟的提议,大概在五到十年前时曾盛行一时。但持有这种观点的人们,似乎很难意识到1987年时全球曾遭遇过的挫折。当时,全球各大经济体的政府曾试图将汇率体系管理推向统一——这似乎是一个激进货币改革的逻辑开端。但是,由于各国政府制定经济政策时缺乏相互合作,结果将货币政策推向可怕的境地,并引起全球利率的大幅上升,而在当年10月份也引发了股市的大崩盘。自此以后,各国政府在汇率改革方面开始偃旗息鼓。市场的崩溃告诉他们一个道理,在经济政策合作方面的伪装可能比任何事情都糟糕。而且到真正需要合作的时候,这种对比就更为明显(例如,直到政府不得不放弃部分经济主权),而进一步盯紧货币汇率的尝试也将会力不从心。 新的全球经济 自上世纪70年代初以来,全球经济最大的变化就是货币流通取代了货物贸易,而这种变化也推动了汇率的发展。受此影响,全球金融市场开始出现了无情的整合,而各国相对不同的经济政策也只能对利率(或对未来利率的预期)产生轻微影响,但却唤起金融资产从一个国家转移到另一个国家的趋势。这些资产转移影响了贸易收入的流动,也影响了不同国家货币的需求和供给,从而影响了全球汇率。随着电信技术的持续进步,这些资产转移的成本将会更低,而速度也将会更快。与并不协调的经济政策相对应,货币流通只能给全球经济带来更多的不稳定因素。 从各个方面来看,国家经济的界限正在被慢慢消溶。随着这一趋势的不断发展,货币联盟的吸引力似乎让所有人都无法抗拒,至少在主要工业国家将会是这样。当然,外汇交易员和政府可能会从心底抗拒。在使用凤凰币的经济区域,相对价格变化的经济调整将会顺利地自发完成,就像今天各大经济体不同区域之间的调整一样。而所有货币风险的缺席都将会促进贸易、投资和就业。 凤凰经济区将对各国政府进行严格限制。过去的有些事情将不可能再出现,例如,一项国家货币政策。凤凰经济区的货币供应将由一个固定的中央银行来执行,它有可能是国际货币基金组织(IMF)。全球通胀率——因此将会限定在很窄的范围内。每个国家的通胀率——都将以此为约束目标。各个国家都应该使用税收和公共支出来抵消需求的暂时下降,但它只能通过借钱而不是印钱来弥补预算赤字。由于没有诉诸通货膨胀税,政府和他们的债权人将被迫比今天更为仔细地来判断自己的借贷计划。这意味着各国经济主权的一大损失。但凤凰经济区拥有一个吸引人的趋势,它在任何情况下都可以剥夺各国政府的经济主权。在一个浮动汇率变化不大的世界里,单个政府也会看到,自己的政策独立性将会受到一个不友好的外部世界的检验。 随着下个世纪的临近,自发的力量正在推动世界走向经济一体化,这将为各国政府提供广泛的选择。他们可以顺应潮流,也可以制造路障。为凤凰经济区准备道路,意味着需要他们减少虚与委蛇的政策协议,并且建立更多实实在在的协议。这也将意味着需要允许并积极推动私营部门在现有国家货币的基础上使用国际货币。人们会用自己的钱包来投票,并最终选择货币联盟。凤凰货币可能将以国家货币中鸡尾酒的方式开始,就像今天的特别提款权一样。然而,随着时间推移,它针对国家货币的价值将不再重要,人们将会选择并使用它,因为它具有购买力方面的便利性和稳定性。 另一种选择——保护政策制定的自主性——这将涉及对贸易和资本流动进行真正严厉管制的新措施。这一过程给各国政府提供了很好的时间。他们可以管理汇率变动,不受限制地部署实施货币和财政政策,并通过价格和财政收入政策来应对由此引发的通货膨胀。这是一个增长——停滞的前景。凤凰货币大约会在2018年左右出现,人们应该欢迎它的到来。 想要澄清的一点是:以上绝不是假新闻。 附报道原文: One world, one money A global currency is not a new idea, but it may soon get a new lease of life Sep 24th 1998 IN DIFFICULT times, people are allowed, even encouraged, to think the unthinkable. Some of the economists who propose capital controls as a remedy for recession in Asia claim to be doing this—but they are flattering themselves. Unthinkable? Malaysia just did it. Dozens of countries still use capital-account restrictions. And it is a cliché of the orthodox “sequencing” literature that a variety of such controls should be retained until other reforms are complete. Really, to think the unthinkable, you have to be bolder than this. So here is an idea: global currency union. Let nobody call it boringly feasible, or politically expedient. Yet, like all the best unthinkable ideas, it has more going for it than you might think—in principle, at least. The idea is not new. Richard Cooper of Harvard University proposed a single world currency in Foreign Affairs in 1984, and he was not the first to think of it. It seemed an outlandish idea, and still does. But much has happened lately to make it worth a moment's thought. The usual way to ask whether countries would be better off sharing a single currency—that is, whether they constitute an “optimal currency area”—is to examine the following trade-off. On one side is the undoubted convenience of a single money as a lubricant for trade and cross-border investment. On the other is the loss of the exchange rate as a shock-absorber for times when one or more of the countries face pressures (an abrupt fall in demand for their exports, say, or a sudden rise in labour costs) that the others are spared—a so-called “asymmetric shock”. In setting cost against benefit, again according to the standard view, the crucial factors are openness to trade and freedom of movement of factors of production. A small open economy has more to gain from the convenience provided by a single currency. On the other hand, if labour (especially) is reluctant to migrate, the need for the exchange-rate shock-absorber is all the greater. Weighing all this, most economists conclude that the 11 countries that are about to adopt the euro are not in fact an optimal currency area. The world as a whole is not even close. So what has changed? The main thing is the current global emergency. This is so serious a crisis that it is likely to prove a paradigm-shifting event, though straws were in the wind already. The emerging-market disaster poses the question, How is the world to live with globally integrated finance? In addition, it casts doubt on what once seemed a good answer: that floating exchange rates are the best way to stabilise the world economy. Shockingly unstable According to the traditional model, a country with unduly high labour costs, and therefore a troublesome current-account deficit, could expect to see its currency depreciate; this would cut real wages, making imports dearer and exports cheaper, thus neatly restoring the economy to equilibrium. But in a world where international flows of capital overwhelm international flows of trade, this does not work. Floating exchange rates destabilise trade and investment by wrenching relative prices away from their fundamental values (that is, from the values that would put the corresponding exchange rates at purchasing-power parity). In the emerging-markets crisis that currently threatens the world economy, exchange-rate movements have not been absorbers of shocks but amplifiers and even creators of them. Governments of small open economies have long known that it is not an option to “leave the exchange rate to the market”. Monetary policy must always keep at least one eye on the currency. But governments have also learnt, in a second big change, that intermediate exchange-rate regimes do not work either. That was the lesson of the European Monetary System debacle of 1992-93 (and, arguably, of the downfall of the pegged-but-adjustable regimes used in Asia until last year). Semi-fixed systems cannot withstand the assault of integrated capital markets: they are prone to self-fulfilling panics. In other words, they too are destabilising. But what does that leave? Let's see. Pure floating is no use. Semi-fixed is no use. So there are two possibilities. One is to turn back the clock on financial integration: then pure-floating or semi-fixed systems might once again be used successfully. That would be enormously costly, especially to the developing countries; and it would be very difficult, because integration is partly driven by technological progress, which is hard to reverse. Still, it is a fair bet that a lot of countries will follow Malaysia's example and give it a try. Otherwise, it seems, the remaining course is to combine increasing integration with perfect fixity of exchange rates—meaning currency union. The fashion for currency boards reflects some of this thinking. Exchange-rate flexibility is more trouble than it is worth, advocates say, so abandon it once and for all. Alas, currency boards suffer big drawbacks all of their own. Whereas a currency union has a central bank to act as lender of last resort, a country with a currency board does not. So these regimes are vulnerable to runs on banks. Currency boards are a poor test of the larger idea. The all-or-nothing, float-or-merge analysis also provides the case in economic logic for the euro: strive for integration, it says, no holds barred. Unfortunately, EMU is a somewhat flawed test as well. It is a political project as much as an economic one, so it will not reveal everything about how well a currency union among independent nation states might work. But it will reveal a lot, and its symbolic importance will be immense. If it fails, not only will that cause enormous political harm to the European Union, but the pressure for global financial barriers will be greatly strengthened. If it succeeds, the case for a global currency union will seem much more interesting. Fine, you say, but how would the world ever get from here to there? Hard to say, admittedly. Find the answer to that and the idea would be thinkable. |

网友评论

网友评论

@好耶网络

Processed In:-0.1953-Seconds, CMS-4Queries-Amazon Web Services

@好耶网络

Processed In:-0.1953-Seconds, CMS-4Queries-Amazon Web Services

您的位置:

您的位置: 【】

【】

[上两篇]

[上两篇]